Select your language to auto-translate:

It is universally acknowledged that the Puritans who founded Boston in 1630 left England fleeing religious persecution from the Anglican Church majority (Anglican was England’s official state religion). But the religious freedom they sought was self-centered; they did not seek universal religious tolerance, but rather freedom to practice their own brand of Protestantism (which became Congregationalism), and to build a closed religious-political society around it. Nowhere was this more visibly noted than in US President William Howard Taft’s 1909 address, where he said “We speak with great satisfaction of the fact that our ancestors – and I claim New England ancestry – came to this country in order to establish freedom of religion,” declared Taft. “Well, if you are going to be exact, they came to this country to establish freedom of their religion, and not the freedom of anybody else’s religion.”

In Puritan New England, citizens had to conform to the Puritan religion and rules, or they were at best second class citizens. Those who did not accept the constraints were prosecuted, often ruthlessly. Roger Williams (in 1635) and Anne Hutchinson (in 1638) were both banished over what today would be considered trivial infractions, but at the time were considered heretical. Later, the Puritans tried to peaceably drive out the Quakers, but when peaceable means failed, whipping and execution followed. Catholics were treated little better and were universally hated and harangued. Only members of the Puritan church could hold office, vote, or even own property. And, the Puritans ability to operate in this manner – largely free from normal English oversight and freedoms – was guaranteed by a unique Royal Charter which gave them significantly more autonomy than was enjoyed by other English colonies.

But, the most intriguing conflict was between the Puritans and their Anglican fellow Englishmen. Even though they professed loyalty to the Crown, the Puritans despised the Anglicans, resisted their involvement in New England’s political affairs, and actively fought the establishment of Anglican houses of worship. One of the key issues was that the Anglican form of Protestantism was much closer to the hierarchical ornateness and ceremony of Catholicism than the ascetic, Calvinistic Congregationalism, the defining standard of Puritan society. Even though Puritan government was open only to Church members, it had a representative assembly and established the Town Meeting management process, with relative autonomy and decision authority given to the local church and town. This is a sharp contrast to the hierarchical British Royal/Parliamentary system, where power was held centrally. The Puritan New Englanders did their best to avoid English meddling or oversight for as long as possible; and they managed to do this for almost fifty five years.

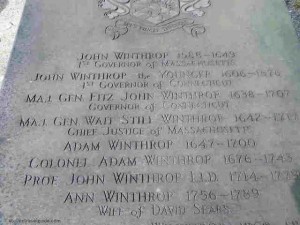

No place in historic Boston does the Puritan:Anglican struggle better play out than with King’s Chapel, the first official Anglican congregation in Boston (King’s Chapel is Stop 4 on Boston’s Freedom Trail and can be visited on the corner of Tremont and School Streets). Anglicans were present in Boston from the beginning, but they were second class citizens without many rights. As early as 1646, Anglican Dr. Robert Child and several others sent a “Remonstrance and Petition” to the Massachusetts General Court, claiming among other things, that they were not free to pursue their religion. In response, the Court admonished and fined them – e.g., their request was summarily rejected. In 1662, a letter from King Charles II to the colony was direct in requiring that “the freedom and liberty should be duly and allowed to all such as desired to use the Book of Common Prayer, and perform the devotions in the manner established in England, and that they might not undergo any prejudice and disadvantage…” The King’s letter was ignored. In a 1664 follow-up, Royal commissioners were sent to Boston to see that the King’s instructions were followed. This delegation also was ignored and King Charles became too involved with issues in Europe to pursue it further.

Finally, in 1676, to follow-up on multiple complaints, King Charles sent Edward Randolph to Massachusetts to investigate. His reports to the King and key ministers clearly noted, along with many other issues, the religious persecution of Anglicans, and included a discussion of British subjects being put to death for religious reasons and the Puritan laws against the celebration of Christmas. Randolph’s campaign against New England ultimately led to the revocation of the Massachusetts Charter in 1684, and the installation of Sir Edmund Andros as Governor in 1686.

King’s Chapel was officially established by the authority of the Lord Bishop of London in mid-1686. The first public service was conducted at the Boston Town House (the precursor of the Old State House) in June, and the official “King’s Chapel” congregation was established soon thereafter. But, the congregation did not have a chapel, and use of the Town House was inappropriate. The same day as his arrival in Boston in December of 1686, Governor Andros started aggressive steps to find a suitable place for worship. Rebuffed by peaceable requests to share space in one of the Puritan meeting houses, in March Andros demanded the keys to Old South Meeting House and commandeered the building for Anglican services – from this point, the building would be shared by both congregations, with priority going to the Anglicans. His requests for land on which to build an Anglican Chapel rebuffed, Andros sized a portion of the town’s burying ground, had the bodies moved, and a Chapel started. The original wooden King’s Chapel was ready in 1689, and the Old South congregation returned to their normal service schedule.

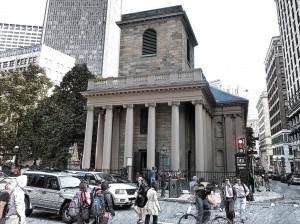

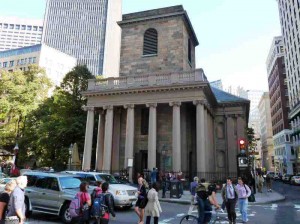

The current granite chapel was started in 1749 when the original became too small. The new chapel was built around the old wooden one so as not to disturb the services. But more importantly, Puritan and Bostonian law also indicated that if the walls were knocked down, the land would revert back to Puritans control. When the new chapel was finished, the old one was dismantled and tossed out through the windows, boxed up and sent to Halifax, where it was reassembled. The new chapel opened for services in 1754.

Far more opulent than austere Congregationalist meeting houses, King’s Chapel was the recipient of many lavish gifts from the British monarchy. King William III and Queen Mary II (1689 – 1702) sent money, communion silver, altar cloths, carpets and cushions. Queen Anne (1702 – 1714) gave vestments and red cushions. King George III (1760 – 1820) donated more silver communion pieces. The silver pieces vanished when over half of the parishioners fled (they were Royalists) when the British left after the Siege of Boston was lifted in 1776.

As the first Anglican foothold in Boston, King’s Chapel presents a number of fascinating and almost poetic paradoxes relating to the Puritan:Anglican conflict. George Washington attended two services at the Chapel: the first in 1753 when he was a British Colonel and guest of Royal Governor Shirley, and second when he was President of the United States in 1789 – he sat in the “Governor’s Pew”. As a replacement for some of the silver that vanished in 1776, Paul Revere crafted several new silver pieces for the congregation as thanks for King’s Chapel hosting the belated funeral for Doctor/General Joseph Warren in April of 1776; Warren died at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June of 1775. Finally, and to come full circle, King’s Chapel became the temporary home for the Old South Meeting House congregation, whose meeting house was undergoing repairs; Old South had been so emblematic of the Patriot cause that during the Siege of Boston, the British ripped out the pews and pulpit, used them for fuel and turned the vacant meeting house into a stable and riding school for British cavalry. The Old South Congregation held services at King’s Chapel for five years, much longer than the King’s Chapel parishioners had held the keys to Old South.

In 1782 the remaining Chapel’s parishioners (there were many Anglicans who were Patriots, not Loyalists) resumed regular services; and in 1787, the first Anglican church in Massachusetts became the first Unitarian church in America. Today, the Church is an independent congregation affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association (which in New England was largely an outgrowth of Congregationalism), but offers a unique liturgy that combines Unitarianism with Anglican traditions. Perhaps this now represents the fitting marriage of Puritan and Anglican traditions and cultures. Huzzah, or perhaps Hurray!