Select your language to auto-translate:

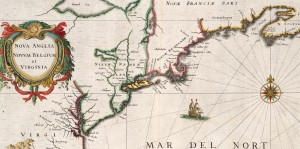

Extracted from 1632 Map of North America – source Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

This is Part 2 of a series about the founding of New England. For Part 1, the Native Americans, click here.

In the 1400’s, even before Christopher Columbus’s fabled voyage to “discover” America, Basque fisherman commonly fished for cod in the area around what was to be called Newfoundland. In 1497, under the aegis of English King Henry VII, the Genovese explorer Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot), while searching for a spice route to Asia, noted a land with a vast, rocky coastline teeming with cod. Cabot called this “New Found Land,” and claimed it for England. By the early 1500’s, it was common for English fishing ships to visit and harvest the cod from this area.

In parallel efforts, in 1501 the Portuguese explorer Gaspar Corte-Real reached what is now the state of Maine and abducted over 50 Native Americans; the Native Americans were sold into slavery. In 1523 the Italian Giovanni da Verrazano sailed into Narragansett Bay, near present-day Providence, RI, and spent over two weeks trading as a guest of the Natives. After leaving Narragansett, he sailed north and encountered the Abnacki on the coast of Maine. In 1534, Frenchman Jacques Cartier “discovered” and explored the mouth of the St. Lawrence river, claiming the area for France. (Cartier was later involved in colonization efforts, but these were abandoned in 1543.)

By the end of the 1500’s, European exploration in North America had become common, but was focused on fishing the plentiful cod. Permanent settlements did not exist and the fisherman-explorers went home as winter approached. Universally, the Europeans noted that North America was thickly settled with natives, generally described as handsome and healthy. And, the area seemed ripe for exploitation. European attention began to shift to the more systematic capitalization of North America. This resulted in the emergence of “trading companies” set up to establish permanent settlements to harvest the riches.

In 1602, English explorer Bartholomew Gosnold established a small post on Cuttyhunk Island (in the Elizabethan Islands near Cape Cod and New Bedford), but had to abandon the outpost as the group had inadequate supplies to last the winter. During this visit, Gosnold is credited with naming “Cape Cod” and discovering Martha’s Vineyard. (In 1607 Gosnold was involved in the founding of Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America.)

In 1605, French explorer Samuel de Champlain, known as the founder of “New France” in North America, helped to found Port-Royal, the first successful French Settlement in North America. In 1605-1606, he visited Cape Cod with plans to establish a French base. This plan was abandoned after skirmishes with the Natives. In 1608, Champlain founded what is now known as Quebec City, on the Saint Lawrence River in Canada.

Englishman Sir Ferdinando Gorges, the “Father of English Colonization in North America”, was planning to develop settlements in Maine – then considered “the Northern Parte of Virginia.” In 1605, he was part of the sponsoring group for an expedition sent to explore the area of New England under Captain George Waymouth. During his voyage, Waymouth captured five Native Americans, who he brought back to England. According to some accounts, one of the captured Indians was Squanto – the same Squanto who was to play a key role in helping the Pilgrims survive their first winter in North America. After 1605, many English voyages carried one or more Native Americans as guides and interpreters.

In 1606, again initiated by Gorges, the Sagadahoc settlement (also known as Popham) at base of Kennebec near modern Portland, Maine became the first English attempt at colonizing New England. It was abandoned after only one year.

In 1609, sponsored by the Dutch East India Company to seek a northwest spice passage, English explorer Henry Hudson passed by the Atlantic Coast and up the river that was to bear his name. Hudson claimed a good part of the territory between Virginia and New England for the Dutch. Their first settlement, for fur trading, was established near present day Albany, New York, in 1615. Dutch colonization efforts did not start until 1624, with the land that was to become their capitol, New Amsterdam, not purchased from the Native Americans until 1626.

In 1614, the English explorer Captain John Smith was ordered by the future King Charles I to sail to America to assess commercial opportunities. Smith reached land in present-day Maine and made his way south to Cape Cod, making contact with natives and mapping out the coastline. Smith called the region “New England.”

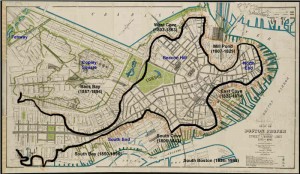

During the mapping, Smith observed the land that was to become Boston. He noted a tri-capped hilly peninsula with an excellent harbor. The harbor was fed by three rivers and connected to the mainland by a narrow neck across a shallow back bay. Called “Shawmut,” it was important to the natives for an excellent freshwater spring.

This all was setting the scene for the first permanent settlement in New England in 1620, the Pilgrim’s voyage to what became Plymouth. But, that is another story.