Virtually every visitor to historic Lexington will start at the Battle Green, the site of the first fight and the ‘Shot Heard ‘Round the World” on the British’ fateful march to capture Colonial military supplies stored in Concord. This short video provides useful context, military dispositions, and pictures of the attractions on and surrounding Lexington Battle Green.

Enjoy.

[embedplusvideo height=”300″ width=”450″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1eWpJmb” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/TMrDDcpeG_4?fs=1&hd=1″ vars=”ytid=TMrDDcpeG_4&width=450&height=300&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=1&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep7250″ /]

Archives for 2013

Introduction to Lexington Battle Green

Musket Firing Demo at Minuteman National Historical Park

Attended a wonderful 3.5 hour walk, led by Ranger David Hannigan, of the Battle Road between Concord and Lexington. When passing by the Hartwell Tavern, we had the opportunity to view this Musket Firing Demo by Ranger Charlie Webster. It was done according to the standard British 1764 Manual of Arms, which was used by both British and Colonial forces.

[embedplusvideo height=”281″ width=”450″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/16CebLT” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/1ZzBaBad75Q?fs=1&hd=1″ vars=”ytid=1ZzBaBad75Q&width=450&height=281&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=1&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep8490″ /]

Click for the Minuteman National Historical Park schedule of events. The 3.5 hour Battle Road Walk, wonderful for those interested in detailed Battle information, is given monthly, June through October.

Guide to Boston’s Unique Geography and Changing Landscape

Select your language to auto-translate:

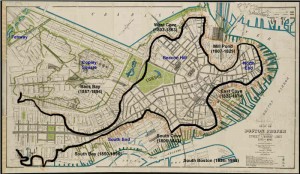

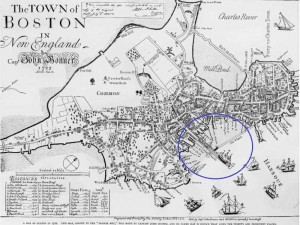

One of the most fascinating and overlooked aspects of Boston is how much the land-form has changed over the years. What you experience today is over 50% landfill. Places you walk, such as the area around Faneuil Hall, were actually part of the harbor when Boston was founded in 1630.

When the first visitors arrived, they found a salamander-shaped, rocky, hilly, peninsula that was formed by erosion at the end of the last ice age. Called Shawmut by the Native Americans, it was small, two miles long and only a mile wide. It’s only connection to the mainland was the low-lying, narrow, wind-swept Boston Neck, which often flooded at high tide and was impassable during stormy weather – meaning the peninsula became an island. During the siege of Boston, the British troops were effectively blockaded into this tiny island, without adequate food or firewood.

The peninsula was dominated by three hills, hence its early name of Trimountaine, which was later shortened to Tremont – a name that lives on in today’s Tremont Street. There was Copp’s Hill (in the North End), Beacon Hill (which had three summits and was almost twice as high) and Fort Hill (which was located in today’s financial district).

[embedplusvideo height=”365″ width=”450″ standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/y3QlGzJW27c?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=y3QlGzJW27c&width=450&height=365&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep8086″ /]

Today’s Boston was created by a series of land reclamation projects, which started in a small way soon after the Puritans arrived in 1630 (you can see the 1630 water line marked in the pavement near the Samuel Adams Statue behind Faneuil Hall).

The major landfill projects took place between 1807 and about 1900, although some reclamation projects extended until almost 2000. Much of the land for the early projects came from the leveling of Fort Hill and from Beacon Hill. The largest project, the filling in of the Back Bay took, spanned several generations between 1856 and about 1894. For that project, gravel was transported in on a specially built train line from Needham, a suburb about nine miles away. One of the first of the second generation steam shovels was used to fill the gravel cars for the trains, which ran around the clock for almost fifty years.

For a fantastic website, which was used to create the animations in the video above, visit the Boston Atlas. It is simply the best place to play with Boston’s changing topography, and was a great source for this post. Also visit the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library – a wonderful source of historic Boston maps, many of which were used in the creation of this post and the accompanying video. For those interested in learning more, there is another interesting post from Professor Jeffery Howe at Boston University; for that post, click here.

Gardner Museum – Venice In Boston

Select your language to auto-translate:

For those wishing an amazing and intimate taste of Italy while in Boston, a visit to the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum is a must. Designed to mimic a 15th century Venetian palace, it was opened by wealthy socialite Isabella Stuart Gardner in 1903 to house her amazing collection of European Art. A meaningful visit can take a little as two hours. For the Gardner’s, website, click here.

Isabella Stuart Gardner was born in 1840 in New York City to a wealthy family and was educated in New York and Paris. In 1860 she married John (“Jack”) Lowell Gardner Jr. and they moved to Boston, Jack’s hometown. After the death of their only child in 1865, the couple traveled extensively in Europe. Their favorite destination became Venice, and they were frequent guests at the Palazzo Barbaro, the home of some fellow Bostonians and a gathering place for artistic of American and English expatriates. The Palazzo Barbaro was to become a major inspiration for the Gardner Museum.

After inheriting a large sum from her father in 1891, Ms. Gardner Isabella began to collect art seriously. She and Jack dreamed of building a museum to hold the collection, which was to grow to over 2,500 pieces – including paintings, sculpture, drawings, manuscripts, ceramics, from all over the world. They were unable to accomplish this together as Jack died in 1898.

Soon after the conclusion of the filling in of Boston’s Back Bay, Isabella Gardner purchased land for the museum and, with architect Willard T. Sears, designed a museum that would evoke a 15th century Venetian palace. The museum opened to the public in 1903. Mrs. Gardner occupied a 4th floor apartment above the museum until her death in 1924. She left an endowment of $1 million that stipulated that the collection be permanently exhibited substantively in the manner that she left it. This is what you visit today.

Perhaps the greatest treasure is the old building itself. Certainly, the art, sculpture and other objects are important and fascinating. But, strolling the building, gazing at sculptures and flowers in the pink-hued central courtyard (supplied from their own greenhouses), the substantial yet ethereal sensations you get walking the medieval halls, is a close as one can get Venice and old Europe in the Americas. It is a unique and accessible opportunity.

In 2012 an expansion wing opened, presenting a surprising contrast to the old building. Visitors enter through the new wing – while there, make sure to walk up the stairs and take a quick look at the Gardner’s unique concert venue, Calderwood Hall. Seating only 300 people across four levels, concert goers are never more than one row back from the performers; the acoustics are superb. For concert information, click here – if you can, plan early as concerts are often sold out.

World-Class Roasted Lamb Sandwich at Flour

Select your language to auto-translate:

Readers know that I’m a big fan of the Myers & Chang family from my previous post – wonderful food, fun and informal atmosphere, friendly people – overall world class. Their Flour bakeries provide sensational and spirited places for baked goods, or a reasonable and delicious lunch or dinner.

One thing not to miss is the Roasted Lamb sandwich. It is a favorite of the Boston foodie blogging establishment, and it lives up to the hype. The Roasted Lamb is served with tomato chutney and goat cheese on a choice of white or wheat bread for $7.99. It is sublime – the lamb tender and not gamey, the lettuce just enough to add a little crispness, balance provided by the tangy rich goat cheese, and then there is Joanne’s bread… But if you are not into lamb, there are plenty of choices.

Owned by Joanne Chang along with her husband Christopher Myers, there are now four Flour baker + cafes: one in Fort Point Channel (these pictures, very near the Boston Tea Party Museum), one near Copley Square, one in the South End, and one in Central Square, Cambridge.

World-class food at a bargain, they make fantastic destinations for lunch or dinner sandwiches and plates. Seating can be challenging at lunch or around dinner times. If you go, don’t forget to try one of her famous sticky buns.

Myers+Chang – John Hancock Never Had Flavors So Exciting

Occasionally, you have a meal that is really exciting. Not necessarily fancy or expensive, just exhilarating with memorable, often new and intense flavors. It might have been at a street vendor in Singapore, the bistro where you took shelter from the rain outside of Paris, the first time you had Thai food, or even that little restaurant where you first tried ceviche in Lima.

View Larger Map

I’ve had these meals, and I just had another one here in Boston at Myers+Chang in the South End. They have been around for a few years, and I can’t believe that it took this long to get here! It is a little out of the way for most Freedom Trail visitors, but the trek is worth it if you like exciting, Asian influenced food.

Public transportation is via the Silver line bus to the East Berkley Street station – SL5 Bus 9, link here. Metered parking is readily available on Washington and East Berkeley Streets. It is also walkable from the Theater District downtown. Although there is seating at the counter/bar, make a reservation, which you can do at Opentable.com, or call them at 617.542.5200.

It feels like a hip diner, e.g., it is not fancy and you don’t need to dress. But, it is fun, funky and has its own style and vibe. Food comes out when it is ready, so don’t plan on traditional coordinated courses. Order dishes to share – two to three per person. Save room for desert.

We ordered a number of the “standards.” The braised pork belly buns came out first. These are little sandwiches of tender pork belly, bao (a green) and hoisin sauce served on dough that almost had the consistency of memory foam – cool and delicious. The taiwanese-style cool dan dan noodles were in a creamy piquant peanut sauce; a great balance to the pork buns. The red miso glazed carrots (serendipitous, as we couldn’t decide what to order) provided perfect contrast. But the piece du resistance was the tiger’s tears (supposedly hot enough to make a tiger cry) – grilled sliced steak in a fiery sauce with plenty of basil and lime. It was not as hot as we expected, but it lingered in our mouths for a while, but not long enough.

Joanne Chang is a fantastic baker (visit one of her four “flour” bakeries if you get a chance), and we elected to share a sticky date pudding w/ginger crème anglaise. Whatever of the crème anglaise wasn’t used on the pudding, I ate with a spoon. I had a Patron XO Café (coffee flavored tequila) and my wife had a Fernet Branca (an herbal aromatic liquor), both on the rocks.

The bill with two drinks with dinner and the after dinner drinks was under $100. On the way out we chatted with the owners, who were both humble and charming; everyone was was welcoming and helpful. The pace on a busy Saturday night was a little frenetic, but it just added to the texture.

All in all, it was a fantastic blending of flavors; unexpected, pungent, sublime and a fun night. Go.

For bargain hunters, Meyers+Chang feature a Cheap Date Night on Monday and Tuesday nights with a $40 prix fixe “themed” menu for 2 people. This is a steal for an amazing culinary experience.

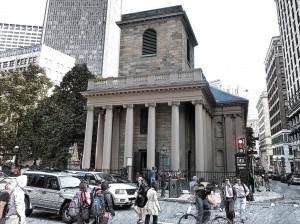

Divine Paradox at King’s Chapel: the Puritan – British Disputes & Role Reversals

Select your language to auto-translate:

It is universally acknowledged that the Puritans who founded Boston in 1630 left England fleeing religious persecution from the Anglican Church majority (Anglican was England’s official state religion). But the religious freedom they sought was self-centered; they did not seek universal religious tolerance, but rather freedom to practice their own brand of Protestantism (which became Congregationalism), and to build a closed religious-political society around it. Nowhere was this more visibly noted than in US President William Howard Taft’s 1909 address, where he said “We speak with great satisfaction of the fact that our ancestors – and I claim New England ancestry – came to this country in order to establish freedom of religion,” declared Taft. “Well, if you are going to be exact, they came to this country to establish freedom of their religion, and not the freedom of anybody else’s religion.”

In Puritan New England, citizens had to conform to the Puritan religion and rules, or they were at best second class citizens. Those who did not accept the constraints were prosecuted, often ruthlessly. Roger Williams (in 1635) and Anne Hutchinson (in 1638) were both banished over what today would be considered trivial infractions, but at the time were considered heretical. Later, the Puritans tried to peaceably drive out the Quakers, but when peaceable means failed, whipping and execution followed. Catholics were treated little better and were universally hated and harangued. Only members of the Puritan church could hold office, vote, or even own property. And, the Puritans ability to operate in this manner – largely free from normal English oversight and freedoms – was guaranteed by a unique Royal Charter which gave them significantly more autonomy than was enjoyed by other English colonies.

But, the most intriguing conflict was between the Puritans and their Anglican fellow Englishmen. Even though they professed loyalty to the Crown, the Puritans despised the Anglicans, resisted their involvement in New England’s political affairs, and actively fought the establishment of Anglican houses of worship. One of the key issues was that the Anglican form of Protestantism was much closer to the hierarchical ornateness and ceremony of Catholicism than the ascetic, Calvinistic Congregationalism, the defining standard of Puritan society. Even though Puritan government was open only to Church members, it had a representative assembly and established the Town Meeting management process, with relative autonomy and decision authority given to the local church and town. This is a sharp contrast to the hierarchical British Royal/Parliamentary system, where power was held centrally. The Puritan New Englanders did their best to avoid English meddling or oversight for as long as possible; and they managed to do this for almost fifty five years.

No place in historic Boston does the Puritan:Anglican struggle better play out than with King’s Chapel, the first official Anglican congregation in Boston (King’s Chapel is Stop 4 on Boston’s Freedom Trail and can be visited on the corner of Tremont and School Streets). Anglicans were present in Boston from the beginning, but they were second class citizens without many rights. As early as 1646, Anglican Dr. Robert Child and several others sent a “Remonstrance and Petition” to the Massachusetts General Court, claiming among other things, that they were not free to pursue their religion. In response, the Court admonished and fined them – e.g., their request was summarily rejected. In 1662, a letter from King Charles II to the colony was direct in requiring that “the freedom and liberty should be duly and allowed to all such as desired to use the Book of Common Prayer, and perform the devotions in the manner established in England, and that they might not undergo any prejudice and disadvantage…” The King’s letter was ignored. In a 1664 follow-up, Royal commissioners were sent to Boston to see that the King’s instructions were followed. This delegation also was ignored and King Charles became too involved with issues in Europe to pursue it further.

Finally, in 1676, to follow-up on multiple complaints, King Charles sent Edward Randolph to Massachusetts to investigate. His reports to the King and key ministers clearly noted, along with many other issues, the religious persecution of Anglicans, and included a discussion of British subjects being put to death for religious reasons and the Puritan laws against the celebration of Christmas. Randolph’s campaign against New England ultimately led to the revocation of the Massachusetts Charter in 1684, and the installation of Sir Edmund Andros as Governor in 1686.

King’s Chapel was officially established by the authority of the Lord Bishop of London in mid-1686. The first public service was conducted at the Boston Town House (the precursor of the Old State House) in June, and the official “King’s Chapel” congregation was established soon thereafter. But, the congregation did not have a chapel, and use of the Town House was inappropriate. The same day as his arrival in Boston in December of 1686, Governor Andros started aggressive steps to find a suitable place for worship. Rebuffed by peaceable requests to share space in one of the Puritan meeting houses, in March Andros demanded the keys to Old South Meeting House and commandeered the building for Anglican services – from this point, the building would be shared by both congregations, with priority going to the Anglicans. His requests for land on which to build an Anglican Chapel rebuffed, Andros sized a portion of the town’s burying ground, had the bodies moved, and a Chapel started. The original wooden King’s Chapel was ready in 1689, and the Old South congregation returned to their normal service schedule.

The current granite chapel was started in 1749 when the original became too small. The new chapel was built around the old wooden one so as not to disturb the services. But more importantly, Puritan and Bostonian law also indicated that if the walls were knocked down, the land would revert back to Puritans control. When the new chapel was finished, the old one was dismantled and tossed out through the windows, boxed up and sent to Halifax, where it was reassembled. The new chapel opened for services in 1754.

Far more opulent than austere Congregationalist meeting houses, King’s Chapel was the recipient of many lavish gifts from the British monarchy. King William III and Queen Mary II (1689 – 1702) sent money, communion silver, altar cloths, carpets and cushions. Queen Anne (1702 – 1714) gave vestments and red cushions. King George III (1760 – 1820) donated more silver communion pieces. The silver pieces vanished when over half of the parishioners fled (they were Royalists) when the British left after the Siege of Boston was lifted in 1776.

As the first Anglican foothold in Boston, King’s Chapel presents a number of fascinating and almost poetic paradoxes relating to the Puritan:Anglican conflict. George Washington attended two services at the Chapel: the first in 1753 when he was a British Colonel and guest of Royal Governor Shirley, and second when he was President of the United States in 1789 – he sat in the “Governor’s Pew”. As a replacement for some of the silver that vanished in 1776, Paul Revere crafted several new silver pieces for the congregation as thanks for King’s Chapel hosting the belated funeral for Doctor/General Joseph Warren in April of 1776; Warren died at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June of 1775. Finally, and to come full circle, King’s Chapel became the temporary home for the Old South Meeting House congregation, whose meeting house was undergoing repairs; Old South had been so emblematic of the Patriot cause that during the Siege of Boston, the British ripped out the pews and pulpit, used them for fuel and turned the vacant meeting house into a stable and riding school for British cavalry. The Old South Congregation held services at King’s Chapel for five years, much longer than the King’s Chapel parishioners had held the keys to Old South.

In 1782 the remaining Chapel’s parishioners (there were many Anglicans who were Patriots, not Loyalists) resumed regular services; and in 1787, the first Anglican church in Massachusetts became the first Unitarian church in America. Today, the Church is an independent congregation affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association (which in New England was largely an outgrowth of Congregationalism), but offers a unique liturgy that combines Unitarianism with Anglican traditions. Perhaps this now represents the fitting marriage of Puritan and Anglican traditions and cultures. Huzzah, or perhaps Hurray!

Long Wharf – the Heart of Colonial & Revolutionary Boston

Select your language to auto-translate:

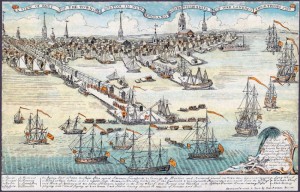

From the beginning, Boston was a town linked to the sea, with its success dependent on maritime trade and industry. And, its most important gateway to the sea in colonial times was Long Wharf. Originally called Boston Pier, Long Wharf construction began in 1711 (when Boston was the largest city in the Colonies), completed by 1715, and at its peak was almost 1,600 feet in length, 54 feet wide, and capable of docking up to 50 vessels. It was, by far, the largest and most significant wharf in Boston and was to play a major role in Boston’s economic and Revolutionary history.

The heart of Colonial Boston was the Town House, Boston’s official town hall, which was at the base of King Street (King Street’s name was changed to State Street after the Revolution). The first Town House was built in 1657 and burned down during the Great Fire of 1711. It was replaced by the current “Old State House” in 1713, and was the location for the British Government until they evacuated Boston 1776. From the Town House, a viewer could look directly down King Street to the end of Long Wharf, see ships coming and going, and keep the pulse of the town.

As illustrated in the famous Paul Revere engraving above, British Troops landed on Long Wharf to help enforce the Townshend Acts in 1768. The oldest structure remaining on Long Wharf today, dating from around 1760 is a building that served as John Hancock’s “counting house” (primary place of business), who in, addition to being the famous signer of the Declaration of Independence, was one of the richest men and a leading merchant in Boston. Today John Hancock’s counting house is the Chart House restaurant.

British troops departed from Long Wharf when they left Boston in March of 1776. It was the landing place for the ship from Philadelphia bringing the Declaration of Independence (first read to the citizens from the balcony of the Old State House on July 18the 1776), privateers and blockade runners sailed from its docks, and its warehouses held military stores.

Today, Long Wharf is a great place to gather tourist information, take cruises of the harbor, and is the docking location for the water shuttles to the harbor islands and the Charlestown Navy Yard (USS Constitution). For an excellent posting on Long Wharf from a series by the National Park Service on maritime Boston, click here. The Aquarium is located at the end of Long Wharf.

Prospect Hill – Key Fortress in the Patriot Lines

Select your language to auto-translate:

When on the night of April 18th the British left Boston on their fateful expedition to capture Patriot munitions in Concord and the “shot heard round the world,” they marched by a hill just outside of Union Square, in what today is the city of Somerville. In 1775, Somerville was part of Charlestown and was located “just beyond the neck” that separated the Charlestown peninsula from the mainland. The hill is called Prospect Hill, and it was to play a key role in America’s fight for freedom from Great Britain.

In the British retreat back to Boston on April 19th, they diverted to go via Charlestown and they again passed by Prospect Hill, but this time in hurried flight and under constant fire from American militia that had gathered from over 30 miles away. (Prospect Hill was one of the last landmarks to pass before the British could reach sanctuary in Charlestown.) There was a major skirmish at the foot of the hill, leading to death on both sides. At the end of the day, American troops were posted on the hill to observe the British as they ferried troops across the harbor between Charlestown and Boston.

In the British retreat back to Boston on April 19th, they diverted to go via Charlestown and they again passed by Prospect Hill, but this time in hurried flight and under constant fire from American militia that had gathered from over 30 miles away. (Prospect Hill was one of the last landmarks to pass before the British could reach sanctuary in Charlestown.) There was a major skirmish at the foot of the hill, leading to death on both sides. At the end of the day, American troops were posted on the hill to observe the British as they ferried troops across the harbor between Charlestown and Boston.

Two months later, immediately after the Battle of Bunker Hill, Prospect Hill was the sight of major American fortification and became the central position of the Continental Army’s chain of emplacements north of Boston. Its height and commanding view of Boston and the harbor had tremendous strategic value and the fortress became known as the “Citadel”.

On July 1st, 1776, George Washington had the new “Grand Union Flag,” the first official flag that represented the united colonies, raised at the top of the Hill. It combined the familiar British Union Flag with 13 red and white stripes. (It was not until 1777 that the more familiar flag with stripes and thirteen stars was adopted.) During the winter of 1777-8, after his defeat at Saratoga, General Burgoyne and 2,300 of his troops were housed as prisoners of war in barracks on the hill. In 1903, a castle shaped monument was erected at the sight of the primary American fortifications. Today, the view of Boston and the surrounding towns is still impressive.

In 1903, a castle shaped monument was erected at the sight of the primary American fortifications. Today, the view of Boston and the surrounding towns is still impressive.

View Prospect Hill – Site of Fighting and Patriot Fortifications in a larger map

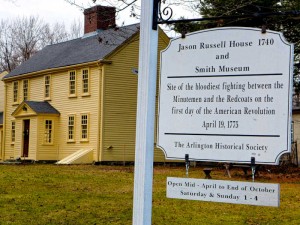

Jason Russell House – Site of the Bloodiest Fighting in the Battles of Lexington & Concord

Select your language to auto-translate:

Arlington, then known by the Native American name of Menotomy, was the sight of the most intense fighting during the British retreat after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. About half of those who lost their lives, about 25 of the Americans and 40 of the British, died in Arlington. Of the American causalities, about half of the deaths took at the Jason Russell House.

The house was built by Jason Russell between 1740 and 1745, but had been doubled in size by the time of the 1775 battle. As it is located on Concord Road (now Massachusetts Avenue), the main street connecting Cambridge and Concord, it was strategic and was gathering site for Minute Men, as well as Jason and some of his neighbors, who wished to contest the British retreat. At the time the British were passing, about two dozen men had gathered around the Russell house and created a mini-fortress.

Although the group had effectively fortified themselves to be able to take pot shots at the main British column marching down Concord Road, they left themselves open to the flankers, who caught them by surprise. Trying to reach sanctuary in his house, Russell was shot down and died on his doorstep. Eight Patriots were cornered and bayoneted. About eight other Patriots effectively barricaded themselves in the basement. Although there were multiple British casualties, a total of twelve Patriots died in and around the Russell house – making this the bloodiest spot in a bloody day.

Bullet holes can still be seen in several parts of the house, which is open for visitors and part of the Arlington Historical Society. There is a wonderful and detailed write-up of the house and its history as part of the Historic New England’s Old-Time New England Articles section, available here.

View Jason Russell House – Site of the Bloodiest Fighting in the Battles of Lexington & Concord in a larger map