Select your language to auto-translate:

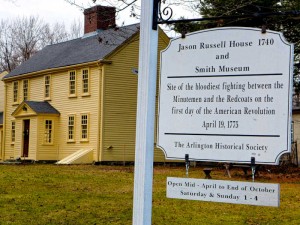

Arlington, then known by the Native American name of Menotomy, was the sight of the most intense fighting during the British retreat after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. About half of those who lost their lives, about 25 of the Americans and 40 of the British, died in Arlington. Of the American causalities, about half of the deaths took at the Jason Russell House.

The house was built by Jason Russell between 1740 and 1745, but had been doubled in size by the time of the 1775 battle. As it is located on Concord Road (now Massachusetts Avenue), the main street connecting Cambridge and Concord, it was strategic and was gathering site for Minute Men, as well as Jason and some of his neighbors, who wished to contest the British retreat. At the time the British were passing, about two dozen men had gathered around the Russell house and created a mini-fortress.

Although the group had effectively fortified themselves to be able to take pot shots at the main British column marching down Concord Road, they left themselves open to the flankers, who caught them by surprise. Trying to reach sanctuary in his house, Russell was shot down and died on his doorstep. Eight Patriots were cornered and bayoneted. About eight other Patriots effectively barricaded themselves in the basement. Although there were multiple British casualties, a total of twelve Patriots died in and around the Russell house – making this the bloodiest spot in a bloody day.

Bullet holes can still be seen in several parts of the house, which is open for visitors and part of the Arlington Historical Society. There is a wonderful and detailed write-up of the house and its history as part of the Historic New England’s Old-Time New England Articles section, available here.

View Jason Russell House – Site of the Bloodiest Fighting in the Battles of Lexington & Concord in a larger map