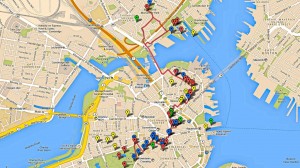

自由之路全长2.7英里

红砖标出的街道连接着

16处重要的历史古迹或“站点”。

它的正式起点是在

波士顿公园,终点在查尔斯顿的

邦克山纪念碑。

在一天之内全部游览完比较困难特别是如果您想参观每个站点。

这里还有许多非正式的

站点 -当您漫步时

您所看到的和您想要了解的。

请记住,这些站点不是按历史顺序排列的,

尽管从地理位置上能看到有些站点很靠近。

大多数的站点是以革命时代主题,但其中一些最受欢宪法号战舰迎的站 还要古

根据您的兴趣和计划,请确定您有足够的时间去参观您想看的。

关于距离,直接从正式的

自由之路起点波士顿

公园到法纳尔大厅大约只有0.6英里(1公里),

不超过15分钟。

从法纳尔大厅步行到的保罗里维尔故居需要10到15分钟。到查尔斯顿站点还需步行15分钟从考普山墓地和旧北教堂。北边的最后的站点到宪法号战舰和邦克山纪念碑还需要和步行10分钟。

从查尔斯顿回到波士顿,最佳建议之一 – 因为

步行一天之后可能感到很乏味

可以坐水上巴士。它从查尔斯顿的宪法号博物馆后面的

海军船厂开始到水族馆和波士顿万豪酒店旁的

长码头为止。很有趣,价格也不贵(成人只需三美金12岁以下儿童免费),这是从港口体验波士顿风情的不错的。

方法 –怎么做的呢?

最推荐的是选择

免费的国家公园导游,从法纳尔大厅

开始,特别是参观北边时,

那是波士顿我最喜欢的地方。

我喜欢的站点宪法号战舰,小朋友们也都喜欢的;旧州府

大楼,有奇妙的博物馆,非常不错的解说。

有还优旧北教堂。

说实话,我并不想省略其它站点,但

如果时间非常有限,那些只能是候选。

祝您游览愉快!

请购买从亚马逊或在波士顿购买“波士顿自由之路 – 最终旅游和历史指南”。它包括自动翻译,交互式地图,智能手机应用程序,推荐路线,小提示,除了参观自由之路外,还有哈佛,列克星敦,以及更多!

从iTunes或Google Play下载免费的应用程序。https://www.stevestravelguide.com/?p=1122