Select your language to auto-translate:

The Boston Tea Party Museum is a fun, entertaining, educational, hour-long historical extravaganza. It provides a good overview of Revolutionary-era Boston history, a climb-aboard visit to a recreated tea-ship (complete with simulated tea chest tossing), the chance to see one of two remaining tea chests from the fateful night (pretty cool), holographic-enhanced reenactments of key events and personalities, and a ten minute film of the events of April 18-19th, 1775 (Paul Revere’s Ride, the battles of Lexington & Concord, and the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World”). Good fun, but unless you crave Disney-style entertainment or are purchasing a package that includes the Museum, it is pricey.

Is it worth the time and expense? Does Boston need Disneyesque historical entertainment? Is the Tea Party “The single most important event leading up to the American Revolution?” Read on…

The Visit

Once you arrive at the museum and have a ticket, you are invited to join the next available tour queue. Tours run every ½ hour and can be pretty full in the summer, so when it’s busy you may want to arrive ½ hour before your desired start. You are then ushered into the “Meeting House” and given a card by a colonial-garbed actor. The card holds the pseudo-identity of an actual revolutionary-era citizen (you may be asked to read a line from card later). Once the meeting starts, and in great in theatrical fashion, your guides explain events leading up to the Tea Party.

[Note that you are kept moving from station to station – there is not much time to linger or explore; virtually every step is choreographed. The guides are well trained, personable, and happy to answer questions, but they speak quickly; pay attention as it is easy to miss something.]

Leaving the Meeting House, you proceed down a gangplank to visit one of the replica tea ships. The replicas are close to the actual Tea Party ships and are amazing. On board, you learn more about the ships and their context, then go below deck to experience what life aboard was like – very tight quarters for the eight men who lived aboard, and these must have been awful in rough seas.

(Click for a wonderful Boston Globe video on the recreation of the ships.)

To make it more interactive for the kids, simulated chests of tea are heaved overboard. (A full tea chests weighed well over 300 pounds.)

On exiting the ships, and while waiting on the dock for your group’s turn to enter the museum, your guide provides additional context to the events and personalities.

Entering the museum, the first stop is a short holographic reenactment of a conversation between two colonial women – one with patriot, and the other with loyalist leanings. The technology is impressive, but the content seems more for show than substance.

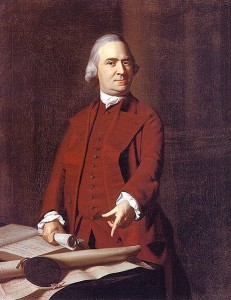

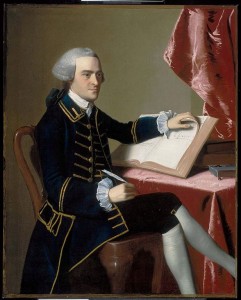

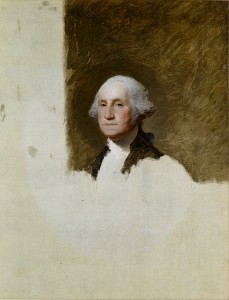

The next room houses the Robinson Half Chest. This half chest (a half-chest contained about 100 pounds) was found by teenager John Robinson the morning after the Tea Party. It remained a Robinson family heirloom until it was purchased by the folks who run the museum. After viewing and learning about the chest, visitors turn around and view a holographic-enhanced conversation between the portraits of King George III and Samuel Adams. This is technically innovative and fun, but a little over the top. The pre-recorded reenactors are entertaining, and what they say is true to the history, but a lot is taken out of context.

The last room, the Minuteman Theater, shows a +/- 10 minute film, “Let it Begin Here,” that dramatizes the events of April 18 and 19, 1775. The film wraps around the audience and is complete with air puffs to simulate musket balls flying by. The tie in is that these events were directly as result of the Tea Party. The reenactments are good and historically accurate, the layout and feel of Lexington Green is particularly good; but the portrayal of the participants is overdone and stilted – the actor portraying John Hancock in Lexington is particularly amusing. (Click for an excerpt.)

After the film, you are encouraged to partake in refreshments at Abigail’s Tea Room & Terrace and visit the Gift Shop, which is stocked with every revolutionary-themed tchotchke imaginable. The only thing missing was the chance to purchase a photo of the visitors with a smiling Samuel Adams reenactor.

Historical Accuracy and Quality

Quite good. The Museum provides a solid and largely accurate overview of the events leading up to the Tea Party and the American Revolution as well as useful context of life in this period. The recreation of the tea ships alone is a marvel and worth the visit.

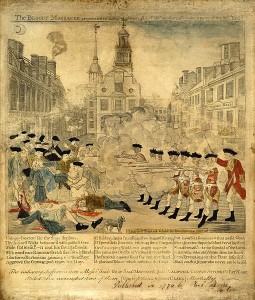

That being said, the events and people are simplified and hyperbolized – both for effect and to pump up the presentation of the Tea Party as “The single most important event leading up to the American Revolution.” No doubt, the Tea Party was a very key event. But it is not the entire story.

I realize that everyone loves a myth with a hero and a villain (Cinderella vs Evil Queen Grimhilde?) – here Samuel Adams vs King George III. But reality is always more nuanced, and the museum makes only anemic attempts to balance their presentation. While this is not necessarily bad, and perhaps even appropriate for a theatrically-themed venue, it is misleading. Suitable for Orlando or Las Vegas, I had hoped Boston might be more thoughtful, or visitors given time to ponder a counterpoint.

Value

Normal admission is $25 for adults, $15 for children – which means a family of four would pay $80 for a one hour show, not including the encouraged refreshments and souvenirs.

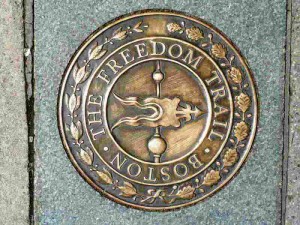

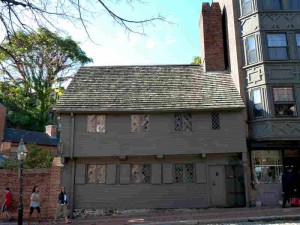

Is it worth it? It depends how much you value this type of entertainment. If cash is tight, there are many better values in town – such as the free Freedom Trail Tours run by the National Park Service, a visit and climb through Old Ironsides, the modestly priced visits to the Old State House or Old South Meeting House, or the behind the scenes visits to King’s Chapel or Old North Church, just to name a few.

If you are considering a visit, a much better deal can be found bundled with the purchase of a ticket from the hop-on-off Old Town Trolley (trolleytours.com), which includes admission to the Tea Party Museum. Historic Tours of America owns both the Tea Party Museum and Old Town Trolley, and they also offer packages with admission to the Aquarium, Fenway Park, and other Boston sites that might be on your short list. Check online as tickets are available at a discount.

The Verdict

I had fun and found it worth my time. My visit was fun, participative, educational, and entertaining.

Is it a “must see?” IMHO, it doesn’t fit that category as there are many other places where you will learn and experience more, are more authentic, and are much better values. If I was bringing children, I would weight it a little more positively as its technology and interactivity will hold a child’s attention and memory more than some other sites; but still not in the must see category.

But I had fun, Huzzah!